A new research effort at MIT offers one of the clearest demonstrations yet of how generative AI, robotics, and human intent may merge into a unified manufacturing loop. Instead of drafting CAD files or prepping machines, researchers asked for objects out loud—a stool, a shelf, a table with one leg—and a robotic system built them in minutes using a small inventory of reusable components. The project demonstrated co-creation as a functioning pipeline in which humans speak goals, AI interprets and designs, and robots execute with precision.

One of the most important findings from the project was that AI can propose shapes infinitely, but only a layered correction system makes them constructible.

See for Yourself

You can watch their robot build these object in real time. It’s very cool.

Turning Speech into Building Blocks

One of the most concrete achievements of the system was its end-to-end conversion of natural language into a physical object. The team used speech recognition plus a large language model (LLM) to extract object intent from phrases like “I want a short chair” or “assemble me a table with one leg.”

When the request wasn’t buildable or referred to an abstract concept, the model returned ‘False’. In testing, it correctly recognized physical objects (e.g., ‘coffee table’, ‘simple stool’) and rejected abstract prompts like “create beauty”. 💫

Once the model identified a valid object, a 3D generative AI model produced a mesh. But the mesh alone wasn’t enough. Generative AI doesn’t respect things like inventory limits or gravity. The researchers, therefore, built a discretization pipeline that converted each mesh into a voxel-based structure of 10×10×10 cm modular components.

Sidebar: Where a pixel is a tiny square in a 2D image, a voxel is a tiny cube in a 3D space. Adorbs, right?

Every voxel that intersects the mesh becomes a buildable component. This transformation is how the digital design becomes a robot-ready blueprint.

Yeah, sorry. That got a little esoteric.

In plain English, this means AI creates smooth, continuous 3D shapes. The problem with that is robots are like, “Sorry, mate. No can do.” They need clear, grid-like instructions that tell them exactly where to place each physical block.

are like, “Sorry, mate. No can do.” They need clear, grid-like instructions that tell them exactly where to place each physical block.

In an effort to meet them in the middle, Team MIT overlaid a 3D grid of cubes on top of the AI-generated shape. Any cube that contained even a smidgen of the AI-generated shape was counted as a buildable component. Each component then became a building block the robot used to assemble the requested object.

The result is admittedly a blocky, Lego-like version of the AI’s design.

We’ll probably look at these rudimentary objects one day the way we look at the world’s first gif.

However, even though these structures don’t have smooth curves, they have one major benefit: Robots can build them. 🦾 This voxel version becomes the construction plan the robot follows step by step.

STAY INFORMED

Get notified when I publish new posts, tips, or projects. 🗣️ Choose what you want to receive. 👌

Making AI-generated Objects Physically Feasible

The research specifically measured how often AI-generated shapes broke physical rules, as well as how much geometric processing was required to rescue them. They identified four fabrication constraints that routinely appeared:

- Component limits: They had only 40 reusable voxel units in inventory.

- Overhang restrictions: Cantilevers longer than three unsupported units were unstable. (In other words, if a part stuck out more than three blocks without anything undergirding it, it became too wobbly to build.)

- Vertical stack stability: Columns taller than four units without lateral support tended to fail.

- Connectivity requirements: Without enforcing connectivity, the robot would try to place parts in midair, so researchers explicitly specified that a robot can only place a component if it is either on the ground plane (i.e., z = 0) or touching a component that has already been placed.

To understand how important these constraints were, the team ran ablation tests—i.e., experiments where they removed one constraint at a time—across four objects: a stool, a shelf, a letter T, and a one-legged table. When the system lacked these checks, many assemblies failed in predictable ways. For example:

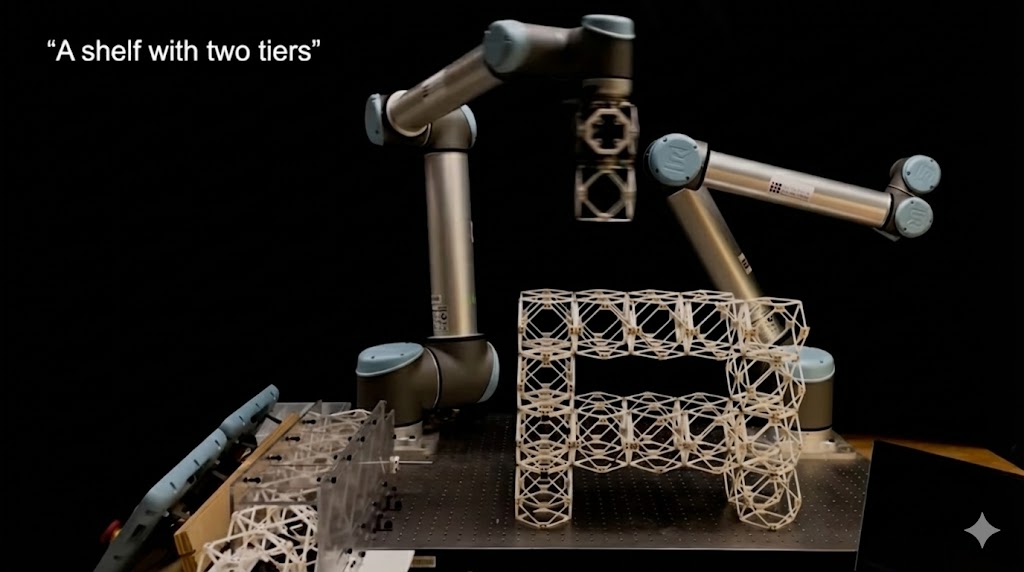

- The AI-generated shelf required 60 components, which was well above inventory. The system had to automatically rescale it down to 32 components.

- The letter T failed the vertical stack test because its stem contained a five-unit unsupported column.

- The stool and table failed without connectivity-aware sequencing, i.e., the robot would have attempted to place pieces in midair.

Once all four constraint modules were enabled simultaneously, all four objects assembled successfully.

One of the most important findings from the project was that AI models can propose shapes infinitely, but only a layered correction system makes them constructible.

From “Stool” to Physical Object in Under Four Minutes

The team ran timing benchmarks that revealed how rapidly physical instantiation can occur when robotics and generative AI were tightly coupled. Using a UR10 robotic arm equipped with a custom gripper and supported by a conveyor that feeds it modular building blocks, the system assembled objects in the following times:

- 1 minute 5 seconds for “the letter T”

- 3 minutes 36 seconds for “a simple stool”

- 3 minutes 41 seconds for “a table with one leg”

- 5 minutes 12 seconds for “a shelf with two tiers”

Every build used the same 40 voxel components, which were disassembled and reused after each experiment. The research noted that printing just the stool on a large format FDM printer1 would have taken about 3 days, 1 hour, and 45 minutes, making the speed upgrade unambiguous.

Human-AI-Robot Co-Creation as a New Manufacturing Model

Because the system works fast and reuses the same materials, it enables a collaborative loop in which users critique, refine, and restate intent. The AI model becomes the design engine, the robot becomes the physical executor, and the human remains the source of direction and judgment.

The core idea is not that robots will replace traditional manufacturing, but that a new class of workflows emerges when physical fabrication moves at the pace of generative AI. This new emerging paradigm allows:

- rapid exploration of ideas without fabrication bottlenecks

- teaching non-experts to design through speech alone

- sustainable prototyping via modular reuse

- potential future extensions, e.g., robot-led disassembly, gesture-based refinement, or augmented reality (AR) previews of structures before they are built

The research shows the beginnings of a production environment where objects are not fixed outputs but temporary states: reconfigurable, recyclable, and generated on demand.

Image credit: Nicholas Fuentes

—

1 ‘FDM’ stands for ‘Fused Deposition Modeling’, and an FDM printer is a type of 3D printer that works by melting plastic filament and laying it down one thin layer at a time to build an object from the bottom up. It’s the most common consumer and industrial 3D printing method.

Leave a Reply